Measuring resilience of adaptation interventions and beyond - Adaptation Futures 2016

The Independent Evaluation Office of the GEF (IEO) recently organized two panel sessions at the Adaptation Futures 2016 conference, which took place in Rotterdam May 10-13.

One of the sessions, chaired by Ms. Anna Viggh - Senior Evaluation Officer with the IEO - focused on measuring resilience. The objective of the session was to share, get feedback and stimulate discussion on the latest resilience measurement thinking, and how this might shape the programme logic of future adaptation relevant interventions, and related M&E endeavours.

The session started with a presentation by Ms. Kristie Ebi of STAP on the Resilience, Adaptation Pathways and Transformation Assessment (RAPTA) framework, who graciously replaced Mr. Anand Patwardhan who unfortunately was not able to make it to Rotterdam. Kristie started with setting the audience's expectation by making clear that there are many definitions of resilience, and with that an equal amount of ideas regarding measuring resilience. The term originally come from ecosystems where it implies returning to an original state. That is not how it is used in climate change, where it has a positive connotation and includes the ideas of coping and recovery. But it's not always clear who or what is being resilience, and what they are being resilient to. We need to focus on what we measure, because what we measure is what we (ideally) end up managing. The monetized impact from climate risk events – like flooding – coming to fruition is very significant, but non-monetized impact on human well-being impact and a whole range of other issues is perhaps even bigger when considering the household level. The question is; if you want to get to a place where after a climate risk even you have a situation of low risk and high resilience, what needs to be done, and what do you need to measure? What kind of metrics are going to be important to track where you are in the process of becoming more resilient?

The Resilience, Adaptation Pathways and Transformation Assessment (RAPTA) framework is a new tool to help you answer these questions. The framework combines a continuum of concepts from resilience, adaptation, adaptation pathways and transformation, and helps you to embed those concepts into projects' design. It aims to work at multiple scales and promotes a structured approach to learning that enables constant improvement and adaptation to change.

The Resilience, Adaptation Pathways and Transformation Assessment (RAPTA) framework is a new tool to help you answer these questions. The framework combines a continuum of concepts from resilience, adaptation, adaptation pathways and transformation, and helps you to embed those concepts into projects' design. It aims to work at multiple scales and promotes a structured approach to learning that enables constant improvement and adaptation to change.

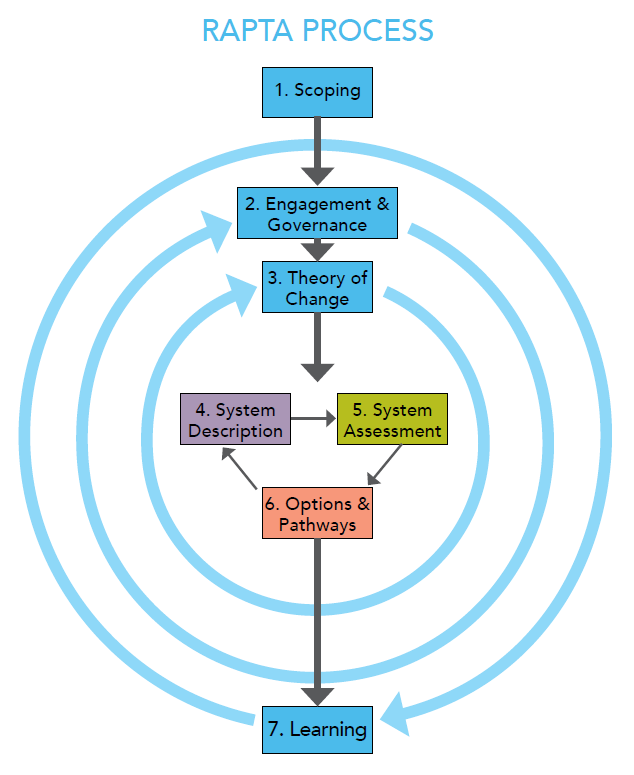

The RAPTA process is an iterative process that has seven linked components. The components shown in blue in the process are critical supporting processes for assessing resilience and identifying adaptation and transformation options. Part of the process (though not visible in the figure) is the development of RAPTA meta-indicators, which report on the application, progress and outcome and quality of the process. CSIRO is in the process of field testing the RAPTA process in Ethiopia where the guidelines are being used by UNDP in Ethiopia through their participation in the GEF's Program on "Fostering Sustainability and Resilience for Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa". The partnership involves Ethiopia, UNDP, CSIRO, and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. Click here for the presentation.

Mr. Nathan Engle of the World Bank Climate Change Policy Team then talked about the World Bank's approach to the M&E of resilience at the project level. With increasing climate change adaptation investments there is a need for increased accountability; are we successful? Are we building resilience? There is also the obligation to share lessons within our own institution and with external communities to learn from our experiences. There has been a proliferation of work on resilience M&E, but there are still some big challenges for resilience M&E; one of them being that we are dealing with wicked problems that demand creative, adaptive solutions. Methodological issues relate to resilience being a latent property of a system, and the need to deal with "multiples" – multiple sectors, multiple timescales, spatial scales as well as multiple potential solutions. The World Bank developed a program called "Results monitoring and impact evaluation for climate and disaster resilience-building operations (ReM&E)" to help enhance climate and disaster resilience of sustainable development operations. A scoping study was done and a review of existing results frameworks in the World Bank showed roughly 1200 indicators being used across 80 resilience focused projects; 200 to 300 of these indicators are specific to resilience and will feed into sector-specific engagement on resilience results monitoring. The ReM&E program is currently ongoing and should result – among others – in a final study report in 2017 on evaluation options for assessing resilience impacts. Click here for the presentation.

A bottom-up approach with a focus on subjective household resilience measurement was discussed by Mr. Lindsey Jones of the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). Lindsey, like the previous presenters, pointed out that there is a variety of adaptation and resilience M&E frameworks (being) developed and choosing which framework to use depends on what you want to measure. But the diversity in frameworks is useful; it gives us different perspectives on the same context. The vast majority of resilience M&E frameworks are objective rankings, in the sense that the resilience measurement is externally verified. A drawback is that, because of the context specific nature of resilience, these frameworks are difficult to apply across contexts. Also, it is not always about what we can measure, about the assets and capacities people have; a lot is about the things we can't see, the intangibles; cohesion, marginalization, risk perception, etc. The idea of the subjective resilience measurement is that people themselves have a good idea as to how resilient they are and what contributes to their resilience, defined as "an individual's cognitive and affective self-evaluation of their household's capabilities and capacities in responding to risk". It is a more engaging way of capturing resilience and it builds on the paradigm shift we have seen in economics, where there is now also an emphasis on subjective well-being. When you agree on what it means for a person or a household to be resilient (as we do on well-being) you can have people self-evaluate their perceived resilience across contexts towards an ‘ideal' picture of personal resilience. Lindsey provided some insights from a Tanzanian survey where a self-assessment of resilience was added to an existing survey. Click here for the presentation.

Lastly Mr. Patrick Pringle presented UKCIP perspective on transformational adaptation, and what the concept means for M&E practice. The use of ‘transformational language' has been growing over time and it seems symptomatic of the broader debate of the need for transformation, which stems for the limits of incremental adaptation. There is a lot of talk about win-win, low regret, and no regret. But how much flexibility is there in the current systems to keep on doing that without challenging the system? Do we need to think about fundamentally different approaches to go beyond the limits of incremental adaptation? There is the risk that we create another buzz-word, which means we need to carefully use it and operationalize it for implementation and evaluation.

From a workshop UKCIP did on transformational adaptation they found that the concept is easy to recognize (we know what is transformational when we see it) but hard to define, which is terrifying from an M&E point of view. A point of departure for M&E is the amount of flexibility that is remaining in existing structures and systems. If we can measure that sensitivity, then we can pre-empt it before the system is failing. We can also track the capacities of a system that are needed to transform. Does it have the capacities and capabilities that are needed for transformation? And if not, can these be embedded into the existing system and its key institutions? You can also track the windows for change; where are the policy windows, the financial mechanisms, undesirable situations that might create a window to think about more fundamental responses other than disaster response. And when transformation is happening we need to ask ourselves whether it is effective and desirable; who are the winners and losers from systematic change?

One of the key characteristics of transformation is the willingness to experiment, which raises some specific M&E questions. We need to use M&E approaches that enable innovation, and enable us to learn from mistakes. Learning, both from successes and failures, needs to feed into next stages of planning. And as much as there can be limits to adaptation, this also applies to M&E; we need to challenge ourselves and be open to new M&E approaches. The learning and action-research M&E approach of DFID BRACED is a good example. If we are to be radical, experimental and ambitious in our change we must be better at learning though M&E. Click here for the presentation.

This session was featured in the daily conference magazine, Daily Adapt Thursday, under the slightly pretentious title "Getting the real measure of resilience". We perhaps have not gotten that far, but it was a packed session with a very lively discussion. Special thanks should go to Deborah O'Connell of CSIRO who was in the room and as one of the authors of the STAP RAPTA framework; she volunteered her time and knowledge on the panel.